|

These three poems are taken from

These three poems are taken from

The Resurrection of the Body

(Smith/Doorstop and Sheep Meadow, 2007)

John Ashbery wrote: 'Vibrant, radiant, Michael Schmidt’s poetry is steeped in modernist tradition (Yeats and Eliot) and questingly new. The result is a passionate discourse that is at once earthy and numinous, from which “flows that unusual grace which is rooted in muscle, / Which comes from the marrow and lymph, which is divine . . .” '

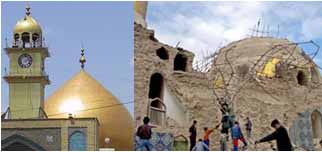

The Golden Dome

22 February 2006

I was there once, oh, forty years ago.

The map does it no justice: the river’s sluggish,

Forgetful; the ruins of the great

City of Samarra are drab and crusted, but what you see

From miles off approaching is the dome, the golden

Dome, rising above the Tigris like a moon…

Among the elaborate geometries that praised

The Merciful, the Compassionate (in His name),

Not far from the spiral minaret that screws the earth

Right into heaven so the muezzin’s voice,

Even as men can hear it, talks to God,

Al-Mutawakkil set a rectangle (measured it out,

Being a tall man, pacing as a king,

His servants and architects drawn in his wake)

Two hundred forty deep, a hundred sixty

Wide. His slaves began to build

Fortress-thick walls with bricks of clay

Washed by the Tigris, hardened in the sun,

Ribbed the structure with forty four stalwart towers

Until it rose higher than the highest house,

Even than the highest house of God.

Within, the blue and gold arcade was exquisite,

With tracery and the words the Prophet said

Woven, inwoven like a choir of birds.

Eloquent especially were the arches facing Mecca.

Compassion, Mercy had an open gate there.

Malwiya was the mosque’s own minaret:

If Al-Mutawakkil paced his way to heaven

Malwiya was the first phase of his journey,

Fifty-two paces up into the sky. When it was done

It was the great mosque of Islam. Samarra.

‘Not briefly the Abassids were approved by heaven.’

It grew, it was remembered and forgotten.

Nasr al-Din Shah, so God would see him,

And re-bless Samarra with His ancient favour,

Gave the gold dome, though not in Nasr’s lifetime

Did its hemisphere crescent the horizon.

A century ago, under Muzaffar al-Din Shah

It was done: gold on the outside, inside

It was just like a blue night sky, a replica

Of heaven itself. Man honoured God by making

A second home for him.

At each corner, the square,

Bearing the tonnes of dome -- clay, tile and gold --

Hosted ornate and very holy graves,

Of Imam Ali al-Naqi (the tenth, peace to him),

His son Hasan al-Askari (the eleventh, peace),

Hakimah Khatoon, Ali’s dearest sister,

And finally the grave of fair Nargis Khatoon,

Mother of Imam al-Mahdi (peace on them all).

Those were the great men, caliph, builder, imams,

The great men and their shadows, mother, sister.

Of the brick makers and slaves there is no record

Except the thing they did, which was well done.

It is the hour of morning prayer.

The square is full of white doves, pouting, preening,

And men with low-arched feet, the poor believers,

The ones who carry God on their bent shoulders

And kneel and touch their foreheads to the ground

And empty out their purses when they go,

All dressed in white too like the plump amorous doves.

As they are praying, murmuring, standing, bowing,

Their eyes fixed towards Mecca and the truth,

They do not sense concealed behind the ornate tombs

Four brothers equal in their other faith.

They do not see the signal, suddenly

The dead Imams (peace to them) and their shadows

Burst from their stone in splinters, heaven falls

In great gouts of lapis, clay and gold

And as when Samson regrew his hair

And rattled the columns, down the temple fell.

Among the sirens and the modern sounds

The shadows come, shadows in their black gowns,

Veiled, but their veils awry and wet with weeping,

The shadows gather and their eyes are red,

Their wailing louder than the circling copters.

Out of those shadows came the caliphs once,

And come the little warriors, the brick-makers and builders,

Out of the shadows come calligraphers

Who write the names of God in tile and gold,

Out of them come the mystics and the Imams,

And lovers, and more shadows like themselves, too,

Some beautiful like Hakimah and Nargis.

The martyrs gloat together as they rise

Past Malwiya and gazing down observe

The gibbous wreck, the great dome broke,

Dust in a plume and a cloud and a haze then settling.

Around the wreck a swarm; as they go higher

Samarra is an anthill, though they hear

Even as they pass into Paradise

The wailing shadows, so like the ones they left

Wherever it is they came from and are gone;

And since their men are dead, the shadows

Here and there, wherever, having spent

Their generations in giving, take flesh, become.

.

|

|

'His father was a baker . . .’

for A.G.G.

His father was a baker, he the youngest son.

I understand they beat him, and they loved him.

His father was a baker in Oaxaca:

I understand his bakery was the best

And his three sons and all his daughters helped

As children with the baking and the pigs.

I can imagine chickens in their patio,

At Christmastime a wattled turkey-cock, a dog

Weathered like a wash-board, yellow-eyed,

That no one stroked, but ate the scraps of bread

And yapped to earn his keep. I understand

The family prospered though the father drank

And now the second brother follows suit.

I understand as well that love came

Early, bladed, and then went away

And came again in other forms, some foreign,

And took him by the heart away from home.

His father was a baker in Oaxaca

And here I smell the loaves that rose in ovens

Throughout a childhood not yet quite complete

And smell the fragrance of his jet-black hair,

Taste his sweet dialect that is mine too,

Until I understand I am to be a baker,

Up before dawn with trays and trays of dough

To feed him this day, next day and for ever --

Or for a time -- the honey-coloured loaves.

|